By Hilary Picken | June 26, 2019 | Language Facts

Translations happen all over the world, all the time. But only now and then does a translation get to change the course of history or define a culture. Here are five which we think did just that.

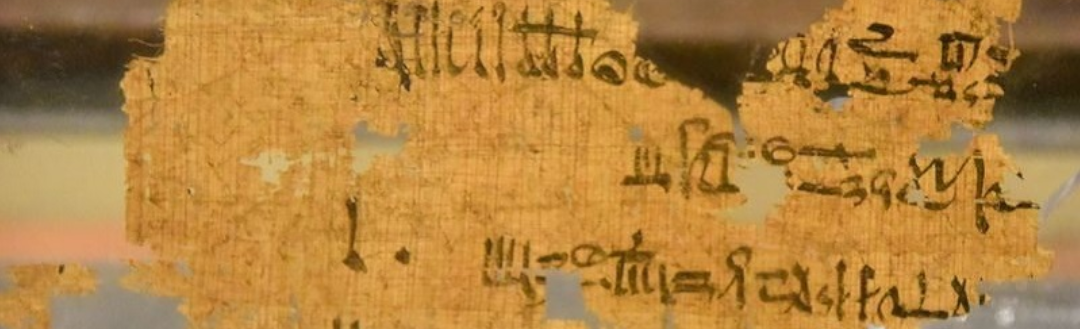

This was a few years ago but it really set the ball rolling. It is the first known written translation in history: the Hittite-Egyptian peace treaty.

After a long war between the Egyptians and the Hittites, the two parties signed a peace agreement, the Treaty of Kadesh (also known as the Eternal Treaty). It was recorded in both the Egyptian and Hittite empires. The Egyptian version was inscribed in hieroglyphics in two temples dedicated to the Pharaoh, while the Hittites jotted theirs down on baked clay tablets.

“Don’t wait for the translation”.

Strictly speaking, this phrase was not actually part of the translation but, as such a large part of such an important verbal exchange, it couldn’t be left out. Don’t wait for translation (Cuban missile crisis 1963). Tensions were running high in 1963 after the US became aware of USSR mid-range missiles being transported into Cuba: just 90 miles from the US mainland and within reach of major US cities.

In a heated exchange at the UN Security Council, American Ambassador, Adlai Stevenson, asked his Soviet counterpart Valerian Zorin if he would deny their existence. As the USSR representative grew increasingly obtuse, Stevenson grew increasingly frustrated, finally demanding “Don’t wait for the translation, yes or no?”.

Given that just about everyone in the free world, and everyone one in the room, had seen the pictures, it was always going to be a tough one for the Russians to deny. The missiles left Cuba.

In this case, it’s a mistranslation, but it got everyone on planet Earth asking, “Is there life on Mars?”

In 1877, Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli noted seeing what appeared to be ‘canali’, on the surface of Mars. Some years later, in the translation of his work, ‘canali’ was taken to mean ‘canals’.

Enthused by the prospect of planetary navigators beyond the earthly realm, scientists scrambled over one another, espousing theories of which civilisation could have completed such feats of engineering. Presumably equipped with shovels.

One man, Percival Lowell, made Mars his life’s work – and revenue stream. His books, Mars (1895), Mars and Its Canals (1906), and Mars as the Abode of Life (1908) were best- sellers. Martians were big business.

Over time a huge sub-culture of books, films and fervent believers developed. From Jules Verne to David Bowie, the world wondered, is there life on Mars?

But it all came to nought. ‘Canali’ is actually a general term to describe channels, which can be part of the natural world and not purposely created. No canals. No Martians. A fact confirmed by NASA’s Curiosity rover which took a spin over the planet in 2012.

Sorry Ziggy, but there is no life on Mars.

An atomic decision…

Translating is not always black-and-white. Multiple outcomes are often possible, influenced by context and opinion. In this instance, opinion led to an outcome of atomic proportions.

Tokyo, July 1945. The Pacific war was drawing to a close and it was only a matter of time before an allied victory. The Japanese, however, had vowed to not go quietly and Washington feared a protracted island-by-island.

Hoping to force a swift conclusion, the US government publicly issued the Potsdam Declaration: a request to Japan demanding unconditional surrender or risk “prompt and utter destruction”. Then waited for a response.

The Tokyo media hounded Japanese Premier Kantaro Suzuki for a statement of his government’s intent. Finally, Suzuki called a news conference and said the equivalent of, “No comment. We’re still thinking about it.” Suzuki used the word ‘mokusatsu’ as his “no comment” response.

Unfortunately, “mokusatsu” can also mean “we’re ignoring it in contempt,” and that was the translation relayed back through the media, to the US. Ten days later, and still with no formal reply from the Japanese, the US followed through on their declaration and dropped the Hiroshima bomb.

The story of ‘Donkey Kong’.

Throughout the 1980s, amusement arcades throughout the western world rang to the sound of a small man jumping over barrels thrown at him by an angry ape. And everyone playing that arcade game wondered where the name ‘Donkey Kong’ came from. Several stories persist. Our favourite involves a contextual mistranslation.

The game’s creator, Shigeru Miyamoto, wished to convey the idea that the ape in the game was big, and a bit stubborn, and a bit ‘goofy’. Aware of King Kong as a big ape, he chose Kong as part of the name. Unsure of the English equivalent of ‘stubborn’ he flipped through the dictionary and landed on the word ‘donkey’ to convey the other half of his meaning.

When Miyamoto first suggested this name to his company, Nintendo, it was dismissed, but gradually the contextually questionable translation began to stick and ‘Donkey Kong’ became the global pseudonym for the game’s big, stubborn ape.

Get insights, information and offers from The Language Factory.